Data Source: BoxRec

Make Money Money…

Boxing is a rough sport, both inside and outside the ring. It may be just as tough, if not more so, on the business side. Everyone needs to look out and make sure they are not being taken advantage of. That goes for fighters, trainers, promoters, and the viewing public. Each of these constituents is at the mercy of the others and can be handed a raw deal at any time. You cannot fault fighters for wanting to make as much money as possible in the brutal and short timeframe they have available to them. It is called prizefighting after all and if someone is willing to put their life on the line you will be hard-pressed to shortchange the value of that.

In recent times no fighter has taken the art of making money to higher levels than Floyd Mayweather, it is even part of his persona and stage/ring name, Money Mayweather. Frustrated at not getting the recognition and accompanying financial rewards he felt he deserved he turned heel halfway through his career and never turned back from cashing larger and larger checks.

Imitation is the greatest form of flattery. Naturally, we have seen several fighters trying to copy the mold. The simplest of these details to pick out and use are the persona and management team. There is also the relentless dedication to your craft but that is not so easily copied and pasted. Instead we more readily see the braggadocio, incessant talk, boasting, and demands for high purses. A savvy management and promotional team can take these ingredients and cook them up into a palatable meal that the audience is increasingly willing to pay for. However, besides image there needs to be substance. What we are looking into is how much substance these fighters have been able to accumulate in comparison to The Money Mold.

Data Source: BoxRec

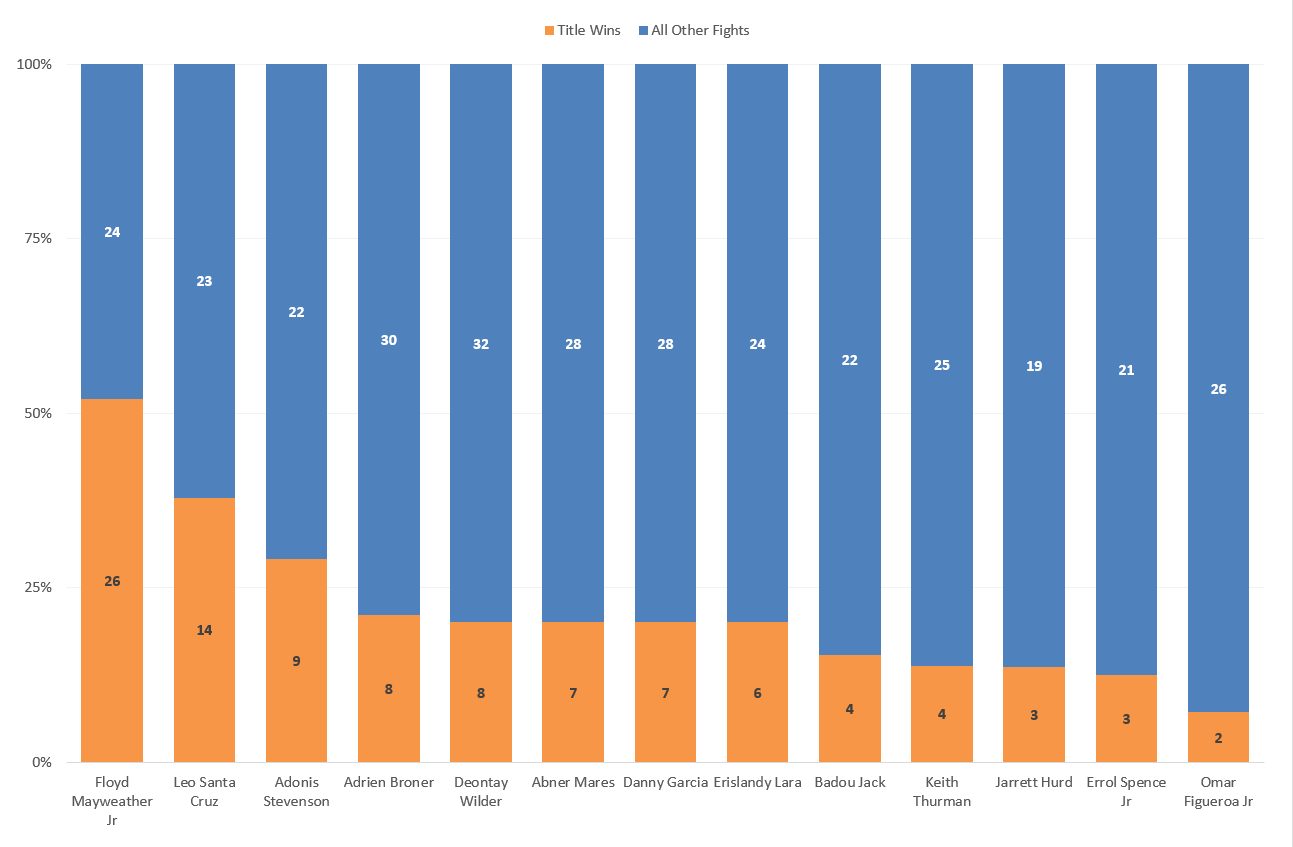

Risk versus reward

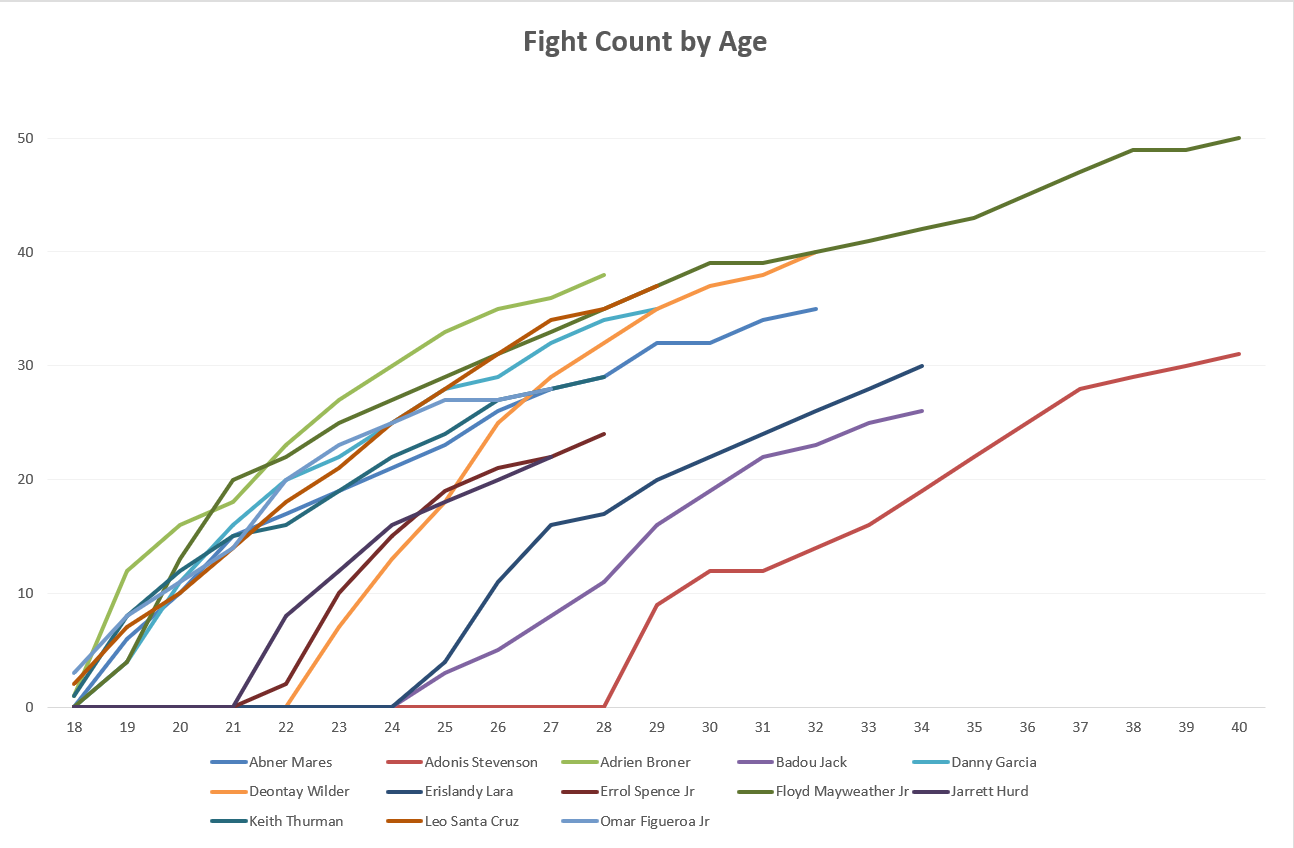

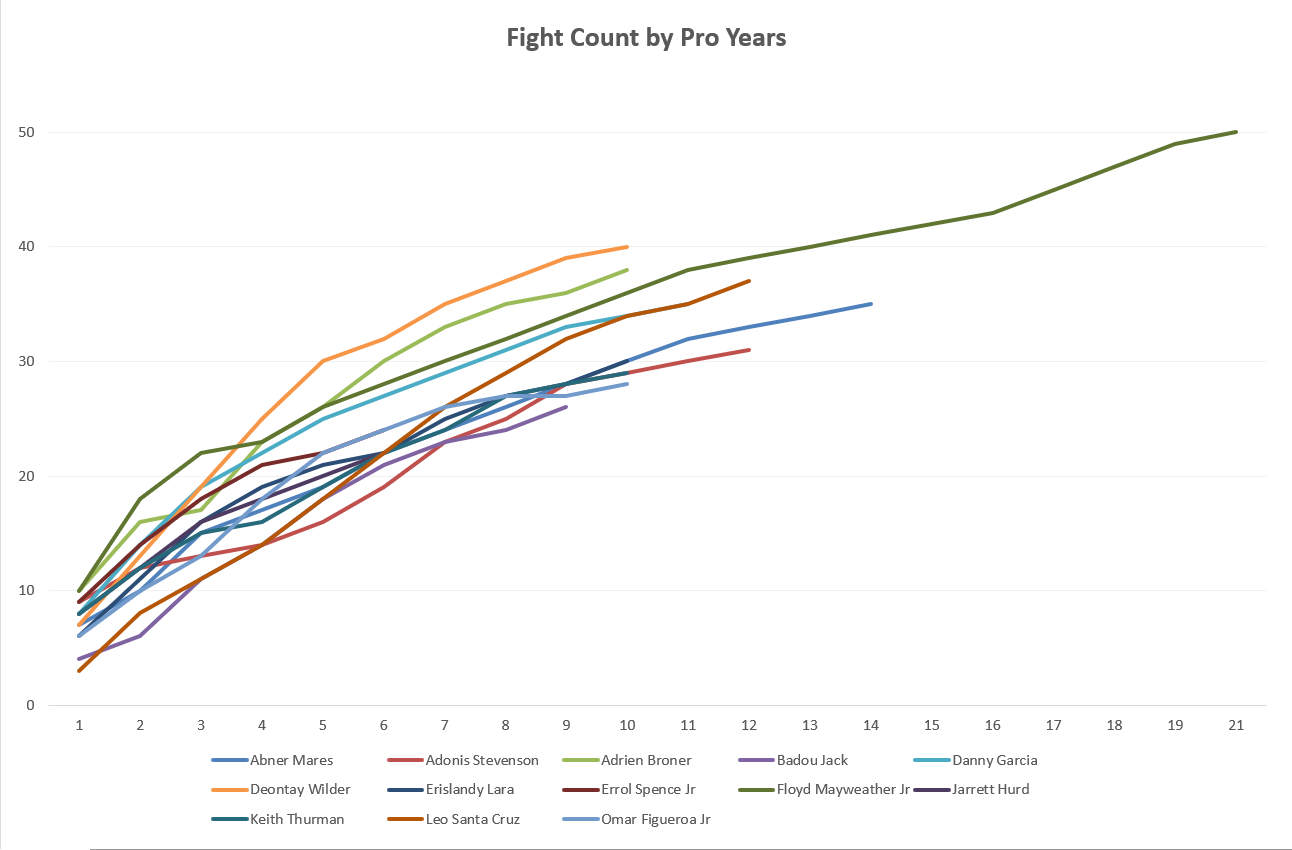

A common criticism brought up regarding the Haymon stable of fighters [Accessed: 9 APR 2018]] is that their rewards are disproportionate to the risks taken. Intertwined is the associated knock that they do not fight often enough. So who they do decide to fight when they finally get around to deciding to fight is a hotbed for debate. This can be viewed as both smart business (it is the hurt business after all) and personal shortcoming. Whether or not we should begrudge the managers, promoters, networks, or fighters is one aspect that can be separated from the underlying proposition: the fighters are not taking enough challenges.

Earlier this year Showtime and Premier Boxing Champions (PBC) unveiled a slew of top fights for the first half of 2018. This was as good a subset to look over as any other. 1

When a measure becomes a target…

Too many fighters appear to want to protect their ”O”, their undefeated record, at the cost of inactivity and lackluster matchups. Most attempts at impersonating the highest paid prizefighter have lead to the perverse incentive of mimicking the symptoms rather than the causes: hard work, dedication. The forthcoming will go a bit toward addressing that by looking at the activity of fighters and their exposure to championship bouts, including their success in the latter.2

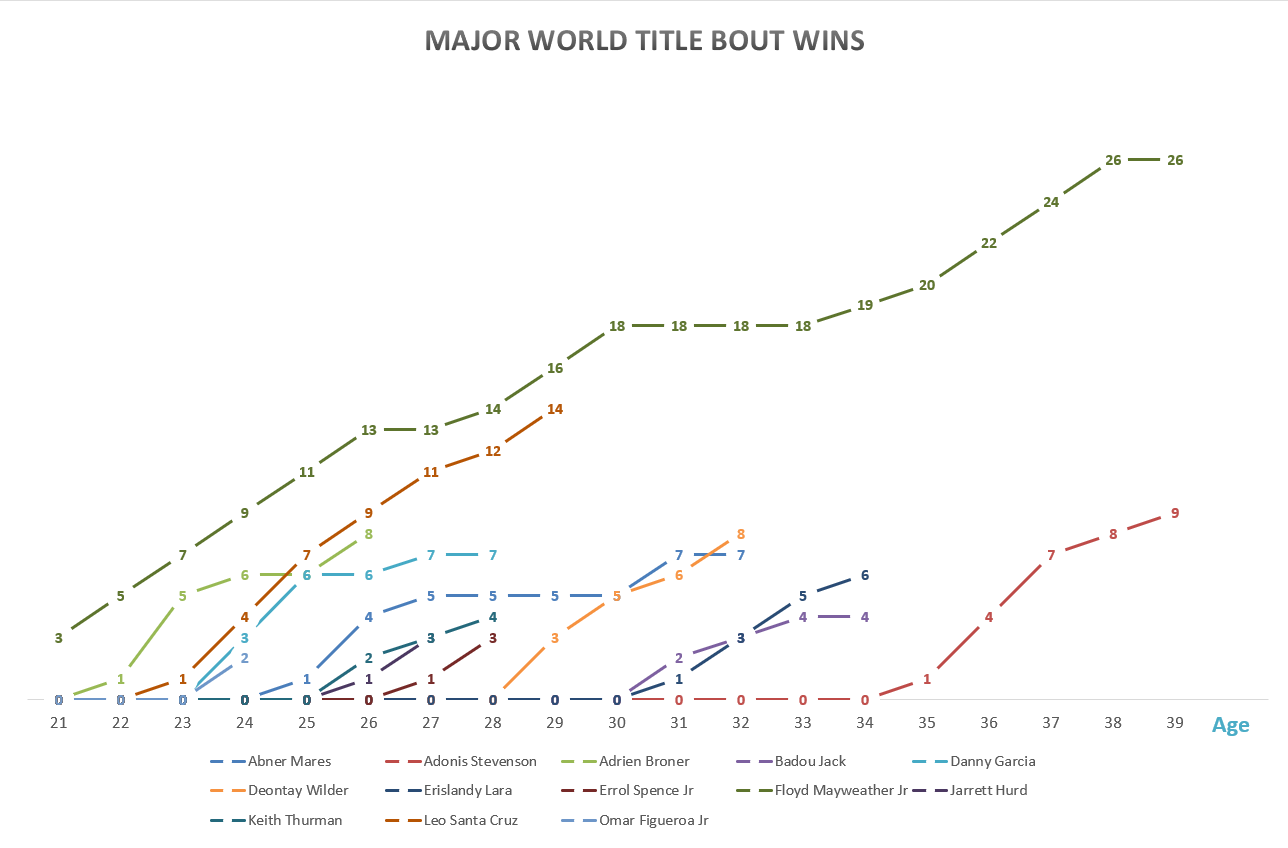

Only Full Major Titles (No Interms, No “Silver” Blah-Blah-Blah)

Only the four major world championship groups recognized by the International Boxing Hall of Fame (IBHOF), as well as the full versions of the titles, were considered for this review:

- World Boxing Council (WBC), 1963

- International Boxing Federation (IBF), 1983

- World Boxing Association (WBA), 1921

- World Boxing Organization (WBO), 1988

Data Source: BoxRec

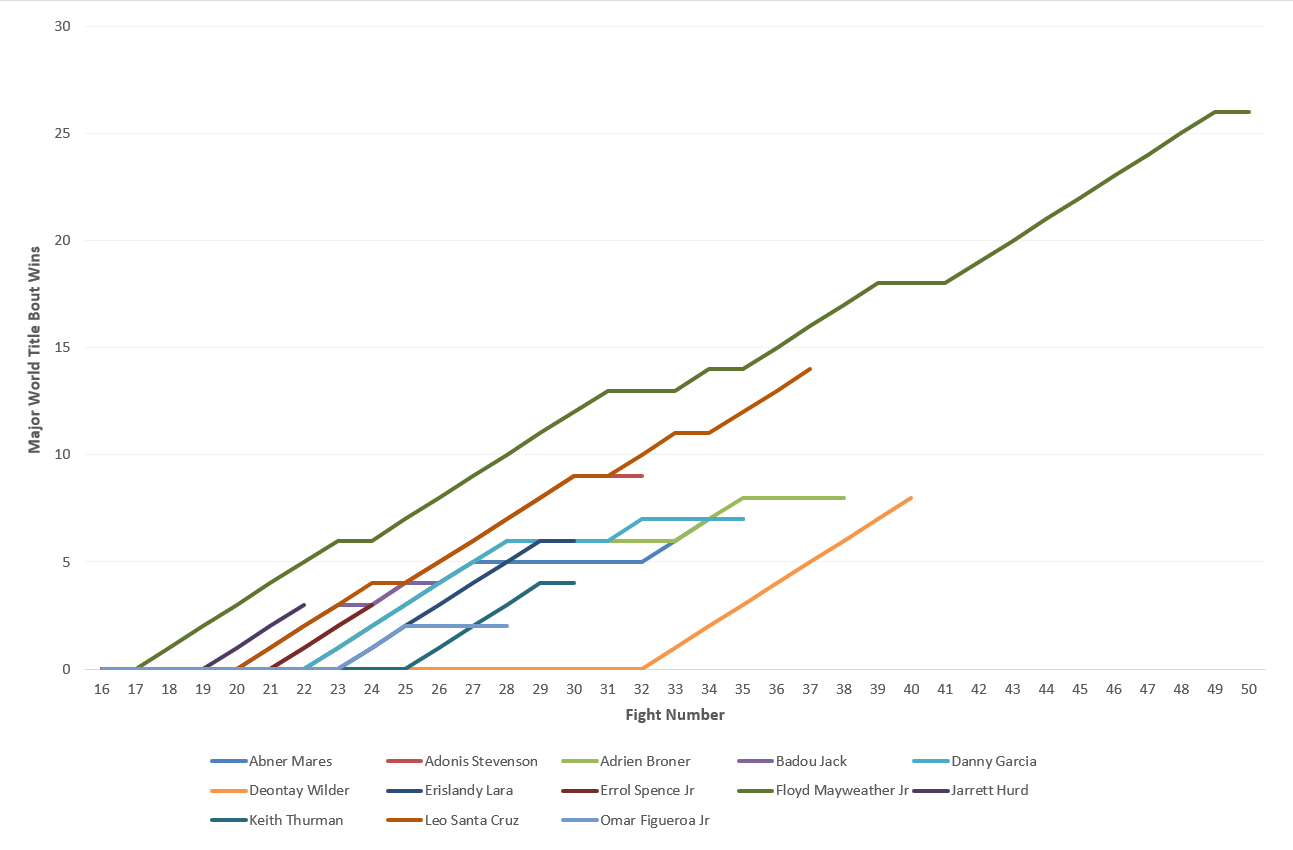

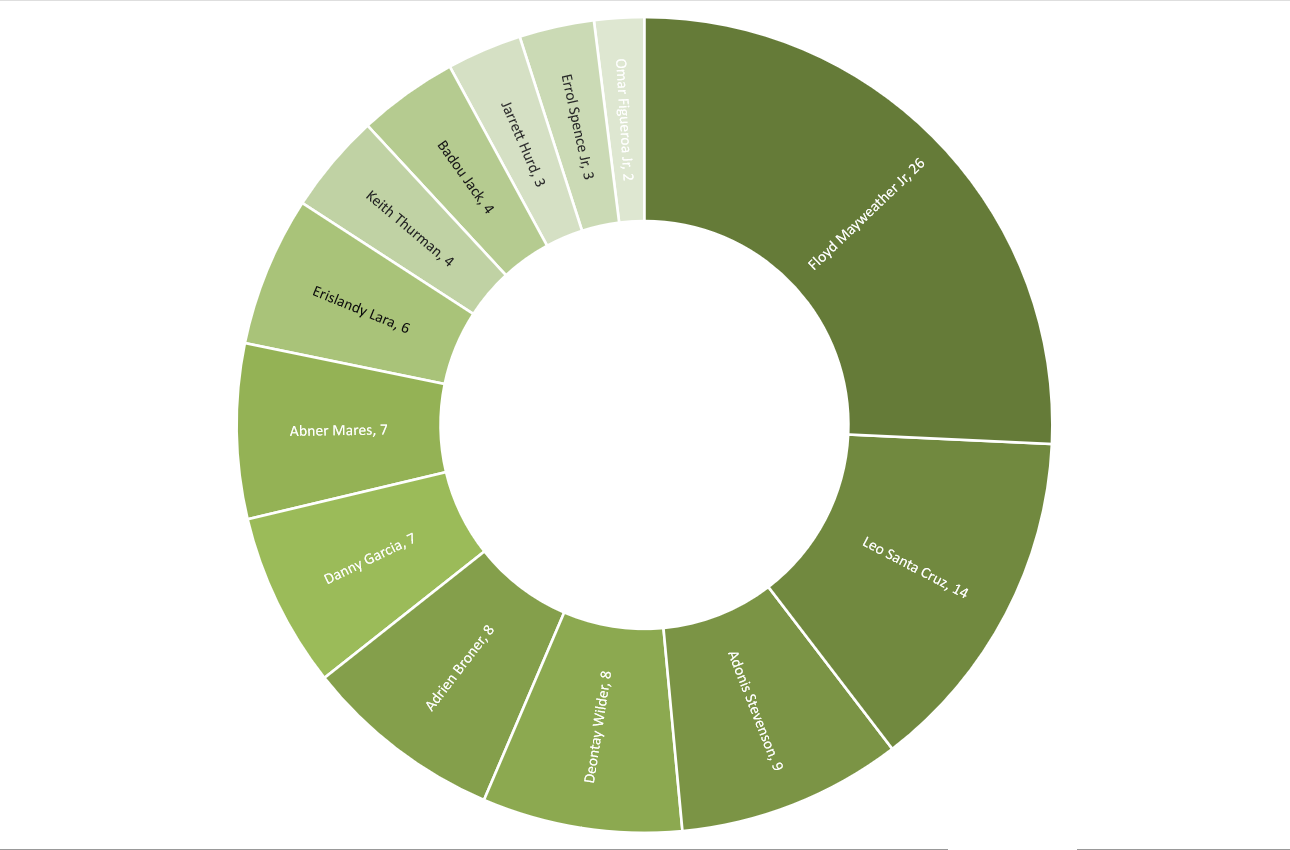

Among this subset of stablemates it is quite clear why Mayweather garnered the big money, attention, accolades, and desired derision upon turning heel. His resume and pedigree backed up his talk. His talk was a tool, as effective if not more so than his defensive prowess in getting the cash, but crucially the former would be useless without the latter. Many of these fighters have serious skills, a couple are likely to be Hall of Famers, but some have arguably grabbed onto the image aspects of building their careers, more so than in-ring results. Each of them has championship experience and wins but they fall short on activity, both by age and number of years at their professional craft.

Consider that Mayweather had 16 championship wins across four weight divisions by the time he fought Oscar De La Hoya and took over the reigns of top PPV dog. Moreover, Floyd had been at it for over a decade. Schooled in the sweet science by both father and uncle, former professional fighters themselves, Mayweather was an overnight success 30 years in the making. Naturally, it was the overnight success part that grabbed the imagination. The life long journey and commitment were relegated to montage material and easily glossed over.

Data Source: BoxRec

Certainly we can point to the different eras of the fighters as an alibi. Mayweather came up in the 90’s while most of the others started their careers a decade later. If we went further back through the eras we would see fighters accumulating even more bouts with each decade we stepped back in time. Go far enough back, think early 20th century, and it is not unheard of to have boxers fight several times a week (Harry Greb), with some rivalries contested several times within the same year (Robinson/LaMotta, ‘43 & ‘45]. Let us set aside fight count then but look critically at the proportion of championship bouts. In a time when there are four major belts per weight class and more weight classes than ever it is a fair criticism to raise as to why there are not more championship wins among the group. Does it all go back to the image, the mythical ”O”?

Data Source: BoxRec

There is One, Maybe

One fighter comes closest to matching Mayweather’s resume on the criteria we have been considering, Leo Santa Cruz. Despite a (championship) loss he remains within striking distance of the Mayweather Moneyline. Should he fight, and win, at the championship level twice a year for the next three years he would match Floyd’s pace at age 31, and pass him at 32. This is a tall ask, as among this group it is more common to fight just once a year once 12+ years into the business. The exception?3

Data Source: BoxRec

NOTES

1

- Feb. 17: Danny Garcia vs. Brandon Rios

- March 3: Deontay Wilder vs. Luis Ortiz

- March 10: Mikey Garcia vs. Sergey Lipinets [left out due to data extraction issues]

- April 7: Jarrett Hurd vs. **Erislandy Lara

- April 21: Adrien Broner vs. Omar Figueroa

- May 19: Keith Thurman vs. TBA

- May 19: Adonis Stevenson vs. Badou Jack at TBA, Canada (neither one managed by Haymon? hmm…; don’t think so, included both)

- June 9: Leo Santa Cruz vs. Abner Mares II

- June 16: Errol Spence Jr. vs. TBA ↩

2 One crucial aspect that will be left out is a ranking of each fighters opponents. This is a first, peripheral glance at the quality of these fighters’ careers to date. ↩

3 Do you really have to ask? ↩