The starting point and inspiration for this edition is an enjoyable three minute video [1] that uses a light touch in covering the steps, certainly a few of the most critical, used by Allagash in producing their wild yeast fermented beers. Our host is Master Brewer Jason Perkins who gives us an overview of the process, emphasizing that while wild yeast is all around us, practically speaking all of the beer in the world is produced with cultured yeast.

In order to brew the beer with naturally available yeast, "resident to this area" as Perkins puts it, there are a couple of differences required to the modern day conventional brewing process.

For these special beers Allagash transfers the boiling wort into an open cool ship vessel, bypassing the now standard cooling process of filtering the liquid through a chiller and dropping the temperature as quickly as possible, instead leaving the liquid exposed overnight across a wide and shallow pool for about 18 hours. This allows the beer to cool and receive natural inoculation from the “resident” yeast through the netted windows of the housing shed. This process is restricted to certain times of the year that provide the required overnight temperatures, most often in November and December.

The wild yeast-infused liquid is then transferred to less than airtight oak barrels (intentionally). If you’re wondering how long before you get to taste the finished product think in the one to three year time frame. All the while small amounts of oxygen is leaving and entering the barrels, adding to the nuances of the brewing and aging process.

The mention of wild yeast and open fermentation always has me thinking of Belgium and more specifically of Cantillon, which I was lucky enough to visit a few years back. The visitor descriptions of open roofs, as much due to holes as intentionally created, as well as cobwebs were true enough.

At the end of the previous video Allagash head brewmaster, Jason Perkins, put a caveat on the idea of brewing from the yeast around us, that the resulting fermentation only works exceptionally well for brewing beers in a few areas of the world. Belgium, the land best known for this sort of thing, was of course mentioned. These two parts, that it only works in certain areas and that Brussels is one of those places (home of Cantillon) , reminded me of a story I saw last year regarding the increased difficulty of brewing in this fashion [2] due to longer summers and warmer autumns.

Cantillon is currently run by Jan Van Roy, the great grandson of the founding van Roy who started the brewery in 1900. According to the current progeny, brewing has been cut back from the eight months his grandfather was doing 50 years ago (mid-October to May) to just five, November through March. There is a real threat of the brewery not surviving if this trend gets any worse. It’s a sad tradition to see end, especially in light of the UNESCO heritage acknowledgment given to Belgian beers, and a clear reminder to the first worlders among us that changes are a brewing in more ways than one and in sometimes unwelcome ways.

If Cantillon folds there will be other breweries to pick up the slack, both current and future, but if the weather continues to change the beer will almost certainly never be the same. The idea of local flavor is discussed in a brief interview on Partially Derivative [3] (last 5 min) with Jeff Stuffing of Jester King. His brewery, on the outskirts of Austin in Texas Hill Country, specializes in farmhouse ales and aims to deliver beers that through local ingredients provide a “sense of place". This is accomplished by using well water, local grains, hops aged on site, and sourcing local micro-flora. Once again leveraging the power of wild yeast.

As previously hinted at this leads to less predictable brewing outcomes and times, so much so that despite their blending from a combination of stainless steel and oak barrels Stuffing says Jester King never make the same beer twice. There’s a certain charm and timely sadness to that idea.

Beer has been so effectively turned into an industrial product by the big boys with their wondrous and impressive modern toys, routinely turning out the same consistent product (Wonder Bread, ahem), that we may be forgiven for forgetting that beer creation was originally a mysterious product thought to incorporate a magical process provided to us by the gods. Even our recent ancestors were not aware of the existence of yeast, evidenced by its absence from the original German Reinheitsgebot.

By Deutsche Bundespost - scanned by NobbiP, Public Domain, Link

In line with a sense of place is another WSJ [4] piece that highlights certain American regional styles, their origins and play off of the local environment and people. While it is made clear early on that brewers of all sizes can source ingredients from around the world the article digs into the "locavore” aspects of brewing popping up and maturing.

An interesting rubric is suggested, that with the downsizing of brewing, a nod later affirmed by references to nano brewing, we are seeing beer become more regional specific. A welcome reminder of the heritage aspect of beer with its origins and proclivities tied to place.

Seven style/region combinations are highlighted:

“the new England IPA, the southern saison, the great lakes gose, the rocky mountain lager, the Cascadian fruited sour, the southwestern scotch and the SoCal session”

My favorite part in each of the examples, even more so than the example beers, is the description of the driving forces behind each style. The reasons range from local harvests, grain and fruit alike, to making drinks to compliment the local food flavors, to even singling out the independent spirit of a locality. The motivations/inspirations are sometimes guessed at but always backed by a human perspective.

Two gem observations are the "the feedback loop of local tastes” and the couching of America’s developing flavors into a longer history and heritage of beer (for instance when referencing the birth of styles by “necessity or… geopolitical jockeying” à la Scottish Ales with their little to no use of hops [debatable]).

Our cataloging sense and taste of place along with the idea of looking at beers through the eyes of regional traits comes at an auspicious time. A time of record breaking brewery counts. After matching the previous national all-time high in 2015, of 4,131 breweries set in 1873, the US has reached a new milestone by surpassing the 5,000 mark, according to the Brewers Association (BA).

A December Fortune article [5] helps put this number into perspective, both historically and contemporarily with other nations. As recently as the 80’s (I don’t know, is that recent?), following decades of consolidation, there were fewer than 100 breweries. That number was quickly surpassed due to a number of reasons I’ve written about before, having to do primarily with home brewing legislation and a consumer trend away from mass produced food stuffs (I’m looking at you again, Wonder Bread).

Public Domain, Link

Brewery counts skyrocketed during the 90’s and early 2000’s, making some clamor about Peak Beer, the article referencing 2013 as a recent example when the count was half of what it is today. Also in 2013, is a BA article from their economist, Bart Watson, stating that based on per capita comparisons with Germany the US could have 5,000 breweries. Well done Mr. Watson (in that piece he distinguished between simple brewery counts and capacity).

Peak Beer aside, and I’m undecided but leaning toward believing it, shower beer being a definite “jump the shark” example, there’s been a slow down in the numbers. To put it pithily, the industry is growing but slowing. Our economist refers to this as a period of maturation in which it is natural for growth rates to fall back to previous percentages. A prompting to look at behavior in previous maturing markets, in like sectors, for relevant activity.

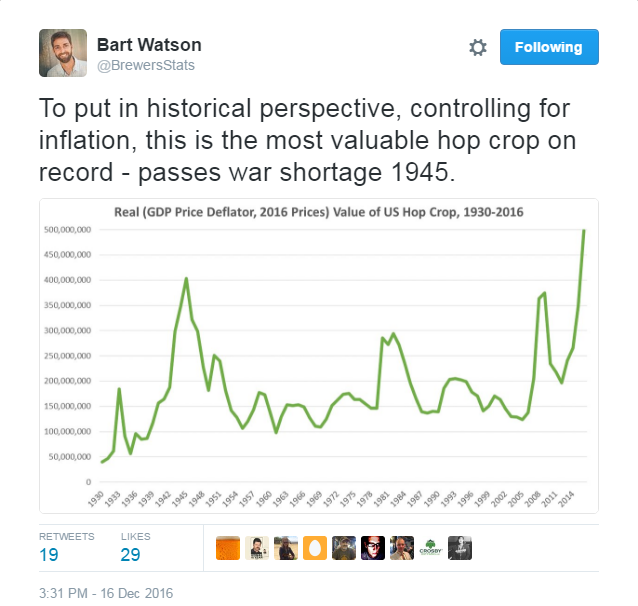

The high number of breweries directly feeds into one of the biggest and final beer stories of 2016: the price of hops. In what is the highest valuation in history, both in absolute and relative terms, we see US hops total nearly half a billion dollars.

According to the USDA the three key contributing factors were increased acreage (+17%, 2016 v 2015), higher production (87 million pounds, +11%), and more expensive hop varieties favored by craft breweries, resulting in a price jump of 31% ($5.72/lbs.). With respect to craft beer preferences the Financial Times [6] article highlights the boom in Citra (2.3 X 2016 versus 2014) and the cratering of Zeus (-⅓), an example of aroma hops being preferred over acid hops, respectively. Underlying all this heady movement is a reasonable amount of soberness (pun!) questioning the sustainability of what we are seeing. This is echoed by the Hop Growers of America’s executive director when reminding people of the cyclical nature of such things and mentioning previous experiences in oversupply.

The article does more than a little hinting at peak craft, using the term itself in the subtitle of the piece. To help substantiate that possibility reference is made to the declines in craft beer sales at the end of 2016, though there’s been overall growth the past 52 weeks.

Growing but slowing, as I previously said. Additionally, the article alludes to the observation that in “certain US cities, especially on the West Coast, … craft beer consumption has reached almost 50 per cent of the market.” This last point I find especially noteworthy as craft beer is often times a higher priced option than standard lagers and substitute alcohols (per/ABV). Cities are where you find higher incomes. Higher rents too. As discretionary spending stagnates or falls, what then?

By Exact source unknown, image likely pulled from existing image on web (Google image search for "fonzie shark jump" shows many

duplicates of same image), Fair use, Link

Notes

[1] Bush, Jeff. “Blowing in the Wind: Wild Yeast Produces Beer With Terroir” The Wall Street Journal . Dow Jones & Company, Inc., 22 Dec 2016. Web. 27 Dec 2017.

[2] “Climate change blamed for putting Belgium beer business at risk” The Guardian . Guardian News and Media Limited, 4 Nov 2015. Web. 2 Jan 2017.

[3] Albon, Morgan, & Spandana. “S2E5: The Double Entendre” Partially Derivative ., 15 Mar 2016. Web 2 Jan 2017.

[4] Bostwick, William. “Where the Beers Are: A Regional Guide to U.S. Craft Brews” The Wall Street Journal. Dow Jones & Company, Inc., 22 Dec 2016. Web. 27 Dec 2017.

[5] Tuttle, Brad. “America Now Has a Record-High 5,000 Breweries and Counting” Fortune . Time Inc., 10 Dec 2016. Web. 2 Jan 2017

[6] Terazono, Emiko. “Craft beer sales slip coincides with record US hop revenue” Financial Times. The Financial Times Ltd., 20 Dec 2016. Web. 20 Dec 2016.

Copyright © 2017 EndlessPint, All rights reserved.